Columbia and HBCU Alumni Reflect on Career Paths, Networking, and Community

Esteemed alumni from Columbia and historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) convened on February 26th, to share insights into their career trajectories, highlighting the pivotal role of mentorship and networking.

Panelists included Taryn Finley (School of Journalism ’15, Howard ’14), HuffPost's Black Voices Editor and Senior Culture Reporter; Brittany Fox-Williams (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences ‘20, Cheyney ’08), Assistant Professor of Sociology at Lehman College, CUNY; John R. Pamplin II (Mailman School of Public Health ’20, Morehouse ’10), Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at Columbia; and Melissa M. Valle (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences ’16, Howard ’01), Mellon Assistant Professor in Global Racial Justice at Rutgers University. The discussion was moderated by Adina Berrios Brooks, Interim Chief of Staff and Associate Provost for Faculty Diversity and Inclusive Pathways.

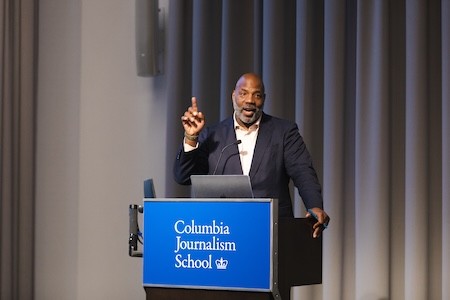

Interim Provost Dennis Mitchell welcomed guests and thanked David Murray, Director of Development for University Initiatives, and the Office of Alumni and Development for partnering on this event. Dr. Mitchell reflected on his journey as a graduate of both Howard and Columbia, emphasizing that his critical thinking and leadership skills, cultivated during his dental degree at Howard, have been instrumental in his roles at Columbia. He then introduced Jelani Cobb, Dean of Columbia Journalism School, a Howard alum as well, who subsequently shared how his double experience at an HBCU and Columbia has been crucially supported by the networks shaped within these institutions.

Watch the full video or read an excerpt below.

Good afternoon, everyone.

It's such a pleasure to be here this afternoon and to welcome all of you. Really thank you for coming: We expect this to be a wonderful, wonderful panel. My name is Dennis Mitchell. I am the Interim Provost here at Columbia University and it is just a thrill.

I want to express my heartfelt gratitude to our distinguished panelists. Brittany, John, Melissa, and Taryn, thank you. We are grateful to you for participating. We are positive that your experience here and your expertise, and insights, and passion especially will truly make an enriching evening for everyone. A special thank you to Dean Cobb for his enthusiasm about this, and for saying yes the moment we were considering it, for sharing his journey at Howard University and his career at Columbia, and for joining us in celebrating a community that embodies both HBCU and Columbia students.

Hopefully you all have some relationship to some HBCU, as well as to Columbia.

A big thank you to the Journalism School itself for graciously hosting us. This is always a beautiful room: every time I walk into this room it makes me feel good, so it’s really, really a pleasure. We also want to extend appreciation to the Office of Alumni and Development, especially to David Murray sitting right here in the front for his partnership for this event. We are grateful for them. They have been working on this for a couple of years and we will do more, ultimately. Also, I'd like to thank my Faculty Advancement team. Most of them are here, especially Adina, Diana, and Greta for the hard work beforehand. But today I know I saw Angela, I know I saw Dror. I'm not sure if I've missed anybody else, but I'm grateful to them and really appreciate their tireless effort and always organizing these events that I throw on them, and then they have to do the work. So that's always the tough part and I'm grateful.

For those of you who do not know it, I'm also a proud graduate of Howard University College of Dentistry. After attending Cornell for undergraduate studies, I attended Howard for Dental School – I was there from 1985 to 1989. Being there offered me the unique opportunity to understand Black excellence beyond the perspective of a student. I saw my Black professors and classmates as long-established and emerging leaders in their fields. I knew I would always have a home, a place to return—and a vital support system. It is the place where I wear my bedroom slippers. I still am a lifelong bison, for those of you who are out there listening and know what I'm talking about.

At Howard, I also found inspiration in my mentors, whose advice has given me the courage to take up space in places like Columbia and make bold decisions. After dental school, I came back to New York for my residency at Harlem Hospital, and then I transitioned into a faculty role at Columbia’s College of Dental Medicine. My research at Harlem Hospital at the time is what brought me to the faculty at Columbia. I did also get my MPH here at Mailman soon afterward. So it has been a fulfilling and enriching life here at Columbia.

My career at Columbia spans over more than 30 years. My initial efforts to diversify the student body at Columbia’s dental school ignited my passion for creating a more inclusive climate and addressing systemic inequities among the students and faculty. This led me to a leadership role in the school’s central administration as Senior Vice Provost for Faculty Advancement, and later on as Executive Vice President for University Life, and now as Interim Provost. And I would not be here without the critical thinking and leadership skills that I started to develop at Cornell, but they really came to fruition as a dental student at Howard. I'll never forget to give Howard its due for helping me in developing my own critical thinking skills.

As we celebrate Black History Month, I would like to congratulate you for taking the time to be here to network with peers and alumni of both an HBCU and Columbia and for making these interdisciplinary connections – and we really hope you do that after the event. I strongly believe they are important, my team believes they are, the Office of Alumni Development believes they are. I am inspired by the energy in this room. Your dedication and enthusiasm are the driving forces behind the future successes of our community.

It is my absolute pleasure to introduce Dean Jelani Cobb of the School of Journalism, let's give everyone a round of applause.

Dean Jelani Cobb:

Welcome. I will tell you that I'm barely mature enough that when Interim Provost Dennis Mitchell (who as my fellow Alpha I refer to as “brother Mitchell”) said “Howard” I suppressed the urge to say “HU!”. You know, it's just like the kind of Pavlovian thing: you hear it and you have to say it. So I'm very happy to be able to welcome you here. I will be brief. I want to thank the panelists. I want to thank all of you for coming out. You know, I'm the Dean of this Journalism School and I think that I am objective enough when I say this is an extraordinary place, and that we have a long tradition of producing many of the best journalists in the world. To be in a position of leadership here is just humbling. Each day, when I walk in and I see that plaque in the lobby which says “From Joseph Pulitzer: the mission of this school is to educate the next generation of journalists, to uphold the standards of excellence in journalism”. Those are my marching orders.

It's very important though that I frame things in context – and this is kind of my history background. None of this would be possible if it wasn't for what I learned, and for the dedication and investment that my professors and even my peers at Howard University made in me. Full stop, plain, simple. I had no idea what I could do. And certainly did not have the confidence to attempt to do any of it. And I'll tell a little story about that in a second.

But I also think I should do a little bit of a roll call here. I know we have a bunch of Howard people (because, you know, that happens). I see a Morehouse hat here. Is anybody else from Morehouse? Alright, so we have 3 Morehouse. .. I was a faculty member at Spelman for 12 years. Right. Special, special affection for Spelman. Do we have any Morgan folk here? Any fam from the North Carolina A&T? All right, all right. So, any place else? Well, where have I left out? Any Hampton, folks? I know, we have that HU (Howard University) versus HU (Hampton University) kind of thing going here. But you know, happy to have some Hampton folk here.

So I'll tell you this one quick story and then I will leave it to Adina Berrios Brooks to begin this panel. You know, my parents were not college educated: my mother went back to college when she was 52, which I was tremendously proud of her for. But at this time she was high school educated, and I commonly tell people my father had a third-grade education. He grew up in a segregated town called Hazel Hurst, Georgia. If you've heard of it means you are my cousin. I somehow ended up at Howard. There's a whole longer story to that, but I won't go into it. I thought this was some sort of cosmic joke. I had no idea that I could actually do this. College seemed an incredible challenge that wasn't true I was up to. My first semester we had to do a diagnostic essay in our English class. And so I came in, I sat in the room and I didn't write anything. For the entire class period, I just couldn't think of anything. So I turned in this blank paper convinced I'm not college material.

The professor said to come to his office on Tuesday. I sit down and he gives me another topic telling me to write an essay. So I sit and I start writing, going through the prompt and following it and he grades it like a doctor reading a chart, reading your report in the lab. He's like “Hmm”. I'm like “What is this?” And then he scribbled something on the paper and I see that he's giving me a B. I thought that B must have been tax deductible, must have been charity, a charity B. For that 14-week semester, we had to write an essay every week. So the diagnostic essay was the first one, the next week we had to write the real one. So I write the first one and I'm shocked. Because he gives me an A. On that one. And I was like, I have earned an A in college. The second week I got an A. The third week I got an A. In the fourth week too. In the fourteenth week I had 14 As.

I called my mother and I said “I think I'm a writer”. And my mother told me later – he told me later to her credit, she didn't tell me this at the time – that those words “I think I am a writer” translated into her head as “I think I'm going to be broke”. Back then she never said this and I foolishly pursued various career choices that have intersected with writing, journalism being the largest plurality of it. But without that professor who took me aside and gave me a nudge, the idea that I could actually do this, I would have had no sense of what I could do. Because then I majored in English and then I was like “I can write essays. I can write books. I can write a doctoral dissertation. I can write lots of things''. When I leave here, I'm going to go write a tenure letter for someone. All of these things that I learned, that confidence was instilled in me. And the last thing I'll say is that part of the importance of the institutions we're in and all the things that we've done, is supported by the network that we built inside there.

And I will tell you that. When I came in, I saw Professor Akinola from Business School. And I was like “I understand you're gonna do a panel with Mark Mason. He's the Chief Financial Officer of Citibank. That's my freshman roommate from Howard”. And if we start talking here, we would all be connected to someone, a professor or a person – that is what the meaning of community is. For all those reasons and for many more than I can go into, it is very exciting and humbling to be able to welcome you all here. Thank you. Unfortunately, I can't stay for the entirety of this conversation because being a Dean means being in five places at once, but thank you so much for having it. And I will now turn it over to Adina Berrios Brooks.

Adina Berrios Brooks:

Good evening, everyone. I first just want to comment on how extraordinary it is to have two leaders who could help us convene here today. We have the Interim Provost here – when I was young I didn't know what a Provost was, so for those of you who don't know, that's like actually a pretty big deal. And then we have Dean Cobb of this esteemed institution, he is here too to welcome you and to share their stories. I just want to thank you both for your leadership and just comment that that's extraordinary. When I was an undergrad here at Columbia in the '90s, that would never have been possible. So I want to acknowledge this moment that you might not find that meaningful, but for those of you who were around here in the ‘90s would never have been possible.

And with that, I really want to jump into the conversation. On our website as well as on the interweb, you can learn all about our esteemed panelists, but for today I'm just gonna give some really short bios so that we can jump in and really hear from our panelists themselves. I'm going to start with Taryn Finley, who is an award-winning Brooklyn-based Huffpost journalist – of course she's Brooklyn based. It would have to be the case, right? If you're Huffpost, that's like basically just Brooklyn based, right?. She is host and producer who highlights stories that intersect race and culture empowering and amplifying black audiences. She's also a proud alum of Howard University and Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. So welcome, Taryn. Next we have Brittany Fox-Williams. She received her BS in Business Administration from Cheyney University, an MPA from SIPA, and a PhD in Sociology from Columbia, and she continues contributing her insights on racial inequality among youth in the US education and justice systems as an assistant professor of sociology at Lehman College. Cuny. Thank you, Brittany. Next, one of my favorite people in the whole world: John Pamplin II. He is currently an assistant professor of epidemiology here at Columbia and is trained as a psychiatric and social epidemiologist at Morehouse College and Columbia. His research investigates the consequences of structural racism in systemic inequity on mental health and substance use outcomes. Welcome, John. And finally, we have Melissa Valle. She's a sociologist who works at the intersection of urbanism, race, ethnicity, and culture. After 10 years working with youth public policies and community development, a dual bachelor from Howard University, 3 master's degrees from Pace University, NYU, and Columbia University, and also a PhD at Columbia, she now serves as a Mellon assistant professor in global racial justice at Rutgers University. Please join me in welcoming our panelists.

So in the order that I introduced you, I'm gonna ask you now to introduce yourself and share a few highlights from your career journey. We're going to start with Taryn.

Taryn Finley

Okay, hey y'all. This feels very full circle because I used to sit in those same chairs, in this lecture hall, and this was only just about a decade ago, so I am really humbled to be back here talking to y'all. So thanks for giving me your ear and the opportunity to do so. Yeah, I am from Dayton, Ohio, if you haven't heard about Dayton, Ohio, then it is exactly what you probably would think it is: just a kind of relatively small city in Ohio – my fellow Ohio up here is nodding because… you know it. So I knew that I wanted to write really early on, especially when I realized that my dreams of becoming a rapper/basketball star weren't going to pan out. I took a newspaper class in high school and it ended up leading me to Howard University, where I ended up studying journalism and interning at amazing companies that really helped put the battery in my back to tell black stories.The the dual experience of being at Howard, among people who look like me, who I didn't have to convince that my stories or stories that I wanted to tell matter, really translated into these internship opportunities at Essence, NBC and local magazines Washington DC.

My networking experience at Columbia kind of started before I even got to Columbia. Actually, l interned with a fellow alumna: I don't know if y'all heard of Sylvia Bell, but she had graduated two years prior and I asked her ”I'm thinking about going to Columbia for the Journalism School. What are your thoughts?”. Our conversation over lunch really transformed my ideas. It made me realize that if I wanted to take my skills to the next level, Columbia Journalism School would be it. Here I really learned a lot about video, audio, and things that translate into my career today. I've hosted at least 5 shows. Right now I have my own podcast called 'I know that's right' in which I talk about culture and entertainment, specifically from the lens of the black stories that I want to tell. And that's something that I never would have thought I would have had the opportunity to do, but I really leaned into my own voice, into my own perspective and experiences to forge my own path in journalism. So yeah, that is kind of a condensed version of my story.

Brittany Fox-Williams:

Thank you. First of all, I'm so excited to be here with you all. Thank you so much to the organizers for inviting me to be here. So I feel like at this moment my career has in some ways come to a full circle. So I'm originally from Delaware County, which is the county outside of Philadelphia. I grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania. And I grew up not too far from where I went to to school, Cheyney University. For folks who aren't familiar with Cheney, Cheney's actually the nation's oldest historically black college. It was founded in 1837. We have a rivalry with Lincoln University. So if you meet a Lincoln graduate they will try to tell you that Lincoln University, so if you meet a Lincoln graduate they will try to tell you that Lincoln was the first, they were not. And so when I was at Cheney, I actually took an intro to sociology course and was completely enamored with sociology, social theory and social inequality. I remember going back to family and friends and saying, “I think I found what my major is going to be, it is going to be sociology”. They're looking at me like “yeah, that's cute. What is sociology and what are you going to do with that?”.

Ultimately I majored in Business Administration. You go to school to become a lawyer, a doctor, to work in business. You go to school to make money, especially if you come from a household where you're a first generation college graduate. So when I graduated from Cheney in 2008 I worked in commercial banking for a couple years. I won't say that it was a waste of time because I learned valuable skills about professionalism, I worked with a great team of women bankers, I learned a lot from them and understood what the professional world looks like. But at the same time I knew that it wasn't the career for me. Ultimately, with some encouragement from my manager, I decided to apply to graduate programs. When I was an undergrad, I received a fellowship from the United Negro College Fund. It was called the Institute for International Public Policy. It's now defunct, but the goal of that program was to encourage. Black and Brown undergraduate students to go into public policy careers. That fellowship came with some resources to apply to many of these public policy programs across the country: Columbia, SIPA was one of those programs and I was fortunate enough to get in. I was very excited and had a fantastic time, I took courses with the late Mayor Dinkins, for example. While I was there, I also decided to dabble in sociology again. So I took a couple of more courses in sociology, one was a race course, and that really sealed the deal for me. After SIPA I applied for PhD programs in Sociology and was fortunate to get into Colombia again. At the same time, a husband was going to the CUNY Graduate Center, so the stars aligned and I found my way back to sociology. So that's just a little bit about my career trajectory and how I got to this point today.

John Pamplin II

Frst of all, I'm really excited to be here. Thank you all for coming, of course. To start I’ll give credit to my mother who graduated from Norfolk State University. When it came time for me to apply to school, it was always a foregone conclusion: “You're going to go to college, you're going to do all these things”. She made me agree that I was gonna apply to at least one HBCU. And it honestly wasn't something that I hadn't thought of until that time.You know, I had heard a few things about Morehouse. I had spent the summer before at Howard. So I applied to Morehouse. It wasn't my top choice. I was looking at some other schools. But then my dad and I went on a college tour to the different schools that I'd applied to. When I stepped foot on Morehouse campus, there was just nothing like it. I grew up in Yellow Springs, Ohio. It's a small, little village just outside of Dayton. And to be frank the pictures of what I thought it meant to be black, and what I thought blackness was, was very limited. I had allowed myself to buy into a very small box of what blackness was. When I stepped foot on that campus it as like if that box was ripped to shreds, and I could see so many different ways of being that were all blackness. There was all, there was no kind of prescripted thing.

It was set: that's where I was going. I was going to be a biology major. I was going to go do medicine because I had some very limited ideas. It was like “You're good at science. You're gonna go be a physician because that's what you do when you're good in science as a kid”. And I got to college. And suddenly I had these professors who were telling me “You could also do this, you could also do that”. And I had the chair of my department, the first week of school, saying me “Look, we have the scholarship program. it's for black men. We're trying to increase the number of black men in PhDs in STEM. You'd be a great fit and you know what at the end of the day even if you decide not to do it, undergraduate research looks great on a med school application. So I said “If you want to pay my tuition, absolutely, I'm gonna do this”. I had a crisis moment right before it came time to apply to med school. I shadowed a physician and I actually hated it. I had been doing this undergraduate research for the last 3 years and I was like “Actually, I really like this. I really like what I'm doing”.

Part of being at Morehouse is having professors who really pour into you. And my professor at that time could see that I was kind of wobbly, I was on the fence like “This is do or die. I have got to apply to these schools”. He said “Look, there's an opportunity in New York. It'd be an opportunity for you to spend two years full time in a research intensive lab. See if this really is the fit that you think it is, before you go down the PhD path”. Which is what I did, and I went back. So I actually came here. I was a member of the Bridge to the PhD program, which is a pipeline program here at Columbia University. And that was my opportunity to live and breathe this research career full time for two years. And after about a year and a half through, I was like “No, I don't like this at all. I was doing behavioral neuroscience research, sort of like animal models.

And I benefited from another lesson that I was taught at Morehouse. I'm sure many of you were taught this at your institutions: That close mouths don't get fed. So there was a gentleman who came, he was listening to a research presentation I gave within the Bridge Program. And came to me afterwards and we chatted. He asked me if I thought I was going to continue doing this line of work. I said "Absolutely not'. He's like “But why not?”. I told him that I really got into this work because I had this passion for human health but also specifically for racial health inequity. I didn't use those words because I didn’t have that sophisticated wording yet, but I just knew I wanted to study why black people always seem to be sicker. He gave me his card saying “Come to my office, let's chat”. His name is Andy Davidson. At the time he was the Vice Provost of the university, but I did not know that when I was telling him all these things, and he was also faculty at Mailman before he joined the Provost Office. We talked about epidemiology. He talked to me about what a research career in epidemiology could look like. I applied to the Masters program. I end up doing my NPH uptown at the Mailman School. I did a summer internship in a full time research lab. I was there for a week or two where I was like “Yep, this is it. This is what I need to be”. I wrote to the professor that day, saying “I think I want to do the PhD program", and the rest is history. Now I am a faculty member at that school.

Melissa M. Valle

Hi everyone. I hear so many similarities to my own experience as we're talking. I don't know if for me it feels completely full circle because a part of it feels like the journey is still ongoing, in terms of figuring out what to do as a career. I ended up at Howard because my dad was a Bison. He passed away three years ago, so… And he was slick, he didn't say “You have to go to Howard”. He would just tell me these stories about how they would be out in the yard, and homecoming, and jokes, and the people, and the connections. When it came time to apply to school, I didn't play anywhere else. I was following in that legacy, but also was figuring out what my own path was going to be. I didn't realize that coincidentally, I also ended up doing similar things as he did. I was like, wait, we both want to hear your book? It was interesting because while figuring out, I didn't know what I wanted to do, like so many of us. I was very mission-driven even when I was younger because it was sort of instilled in me that you're here for a purpose, and the purpose is to help black people. To help people who are suffering, people who are oppressed.

But part of it was “Well, what major is that? I don't know what major that is”. And so I was looking at a course that I went in undergraduate, and I saw this course on 'Black economic development of something' (because this is Howard, right?). So it was on. I was like “I'm gonna take that”. And then I was looking, I was like “These afroamerican studies courses are really interesting, I want to take the ‘Commercial exploitation of the Third World’ l, I want to do that”. I ended up saying “Well, if I take this and it has these prerequisites let me just double major”. I'm a major in economics. And I thought that I really wanted to take these FAM courses, then as well major in that too, and hence I got the dual degree there.

But part of it still was figuring out. I really wanted to major in photography, but then my roommate, who was from Jersey like me and we went to high school together, was like “Girl, you're not making photography”. So instead I became the photography editor of the yearbook. There's a way that you still can get those needs met, if you want to have creative pursuits – although part of me still thinks that you need to go where your passions are, and figure out how to translate those into things that are meaningful in the world, you know. So I ended up in economics, FAM. Like other people, I had these mentors and had these internships. I had a black woman who was an economics professor, she was my Econ 1 professor and she was like “You know, you're really good at this Econ thing. You might want to do this Patricia Roberts Harris Fellowship”. That was a new initiative at the time, and you could go intern with local community development corporations. So started working with them and doing work on anti-gentrification, and then I turned at the Human Rights Watch. And again, I was still trying to figure out what the thing is. And while I was there, one of my home girls in one of my organizations sent me an email about this Woodrow Wilson PPI thing at Berkeley for the summer. It used to be a program which was at Princeton, Michigan, Berkeley (they changed the name, it's now PPIA). They used to give full funding for that program, but then because of all these wonderful anti-affirmative action propositions in California, you still have to pay a partial funding if you decide to go to a public policy program. And so I decided to go.

I did Americorps for a year. I was going to do the Peace Corps, I got accepted, but I declined. I was still trying to figure out what is the way, like Peace Corps, mirror core, public policy, then I was into community, I was a public policy director of Abbott City Development Corporation in Harlem. And then I got fired from there. And then, we meandered. So then I was like "Okay, I'm gonna do something else. I'm gonna go into education". So I became a public New York City teaching fellow, I worked on the Lower East Side for four years. I was a special needs teacher. I was like “This still not it. This still isn't it. I need to unpack this mystery. Why are we in this condition? Why is it that in the Lower East Side of Manhattan the area of median income is $19,000? What are we doing? What's happening?”. And still wasn't feeling like I was getting those answers. I had never taken a sociology course. I was thinking “Who's asking the questions? Who's doing the work?”. I remember being in this room for one of these conferences. I started sort of being like a conference groupie. I was hanging out at sociology conferences here and there and I'm like “Does this feel right?”. Because when I was reading newspapers I really noted that those sociologists kept being sighted for the issues that mattered to me. So I decided to apply for a sociology program and I ended up here.

Again, I was still trying to figure out what was going to be the thing. And then you start going through what your dissertation is going to be about, and where you are going to be. When I was at NYU, I decided to do local policy. I remember that during the spring break we were in the Bronx doing work, while the group that was doing the international work was in Madagascar. I was like “Wait a second. We got a free trip up town and y'all got a free ticket to Madagascar?". And I was like "All right, I'm gonna do international work next time, I'm going to travel this world for free”. So that's what I ended up doing. I decided to do international work in Latin America. I'm African American, Puerto Rican. I was thinking about race and the intersections of race and nation and gender, about conceptualizing the idea of justice and liberation. I ended up going to do my dissertation work in Colombia on social movements. All of a sudden, I'm in this neighborhood and I realize I won't be living here in 5 years due to gentrification. And I decided that I'm gonna come back here. And again, why did I know so much about gentrification? Because of that first internship that I did in DC. I decided I wanted to work in Harlem doing anti-gentrification work for Abyssinian. These things just kind of kept coming up and that's how I ended getting a Fulbright at Columbia. And so now, I'm still trying to figure out – surprise surprise. I'm jointly appointed in these multiple departments. I'm in African Studies at Rutgers North, and I'm in the sociology and anthropology departments. It’s a journey based on, like everyone else, the internships, the mentorship, and then that's just how my heart works. No matter where I go, Howard is the base, is the root, is the love, it's a deeper connection than any other institution I think probably ever go to.

Adina Berrios Brooks

Thank you so much and God, I want to have a drink with all of you all the time. Maybe after we can talk. I was an urban studies major and I do all the sociology, I love it. So my next question is two-part, and you can answer one or both of the questions. What are there key steps or to decisions that played a significant role in shaping your career path? In which ways did you manage to leverage the benefits of both the HBCU experience and your experience here at Columbia? I don’t like to use the word leverage, but I will use it for lack of a better one. Maybe this ties into the key-decision part, which is why I lump them together. But if they're not, that's fine too.

Anyone can jump in here.

Taryn Finley:

I love what y'all said, there are parts of my story that I resonated with different parts of what you all said. One thing that is really interesting is that I wasn't even trying to tell black stories on purpose. It was just a thing of me knowing that these were the stories that mattered to me. I went straight from Howard to the Journalism School at Columbia. I knew I wanted a career in magazine, digital media-ish. I wasn't super clear on what that looked like or where that was. My dad also was “Girl, you are about to be broke. I don't know why you are trying to do journalism”. But I was stubborn and this is what I wanted to do. My first week starting here at Columbia, Vine was a big thing, and I remember scrolling on Vine every night. That same week Mike Brown was shot. Me sitting in reporting classes, I felt like there was such a disconnect with what I was seeing on my timelines and the feelings that I was having, with the conversations that my friends and I were having. Shout out to our reporting professor because she was amazing. I remember bringing up the fact that, despite knowing that that was just an introduction, this is going on now. This is breaking news. And this isn't something that needs to be relegated to just my timeline, or black Twitter (that was super early back then), or the hashtags. And I was seeing a disconnect not only in the classroom, but also in the stories that I was reading on New York Times on whatever national publication. So I made a decision that I was going to make sure that the stories that I want to see are told, I'm telling them in every reporting class that I take. So I took an identities class – I believe it was ‘Identities and Humanity’, but I'm probably messing up the name, it's been 10 years and I think that's too long honestly. But I remember taking classes and interweaving Black stories in the assignments. In the back of my head, I had a previous boss at an undergrad internship who told me “You'll have all the time in the world to tell black stories. Why don't you tell these kinds of stories instead?”. And I'm like “Why? That doesn't make sense to me”. No one ever says that when you're, in international affairs or politics or sports or so.

That question just kept coming up and so that first week of not seeing this story, this young black boy, this teenager whose body was in the street, the fact that wasn't on everybody's mind and tongue, and that wasn't at the tip of everybody's feelings, that hurt like hell for me. And so I made it my mission to make sure that I was telling these stories, not just the stories of pain, but also the stories that sell our culture, celebrate our hair, celebrate our dialect and in everything in between. So I think that answered the first part of the question. About leveraging the HBCU plus Columbia combo – like you say, Melissa – at Howard, my back just was just as straight as ever. There's something about that experience that felt so spiritual and reinvigorating: what my thoughts were, what black stories could be, what black life could be, what my own stories could be within journalism. And it also checks my own preconceived notions about this idea of objectivity, because when we think of objectivity in terms of journalism, what we are thinking about comes from a white male-dominated lens. I was fortunate to have that challenged specifically by professor Ron Nixon at Howard. He's amazing, he is a force and he pushed me. I walked out of his class probably in tears a few times, but the way that he pushed me to become a better journalist was what reassured me that I was ready for Columbia. And to never question that Columbia wasn't the place for me.

So when I stepped onto this campus, I didn't question myself. And that was just a gift that I was able to bring into corporate America, into interviews with people who may have been like “What is this six-foot black girl doing here, covering this trial when she was the only one that looked like her in the room?”. So I appreciate him so much for giving me that, and Colombia for really reinforcing the tools that I really need, especially in a multimedia landscape. The things that I learned as far as not only being able to double down on reporting, but also making sure that I knew video front and back, that I knew audio and and knew what it really looked like to put together a good feature story. Things that I still carry with me right now to this day, and are just so invaluable.

Adina Berrios Brooks:

Sounds like a magic combination.

Brittany Fox-Williams:

I'll talk a little bit about an experience that kind of brought me here. I mentioned I'm from the suburbs of Philadelphia and I went to predominantly white schools. In Morton, Pennsylvania, we had a little community, a proudly black community, but our town was too small to have our own school so they bussed us to the neighboring white community. And I could say that all through those twelve years, it just felt very isolating. You have this sense of not belonging, right? I didn't necessarily enjoy going to school until I found a black woman educator in high school, who I finally felt like I could relate to. She was from my community and took me on as a mentee. That is something I really reflected on like when I was thinking about what I want my focus to be in my PhD program? I remember even having conversations with my husband at the time. We're writing these essays for grad school, we're trying to get in, we are trying to decide what our dissertation topic is going to be. For me, it was understanding black children's experiences and stories through school – I think that something that we all kind of share is understanding black stories and who gets to share that narrative and be a part of that and have their narrative.

For me going to Cheney, or going to HBCU, was really a no-brainer, I was completely settled in the fact that I was going to an HBCU. I wanted to be in a place where I felt like I could just be me and be around other people who look like me. When I got at Howard, of course, I was completely shell shocked, becauseI haven't been to a homecoming or sat in a cafeteria where everyone looked like. But after the first couple of weeks it just felt like home, and always felt like home. Very much like what Taryn said, l feel that when I came to Columbia, that experience gives you a sense of self. You feel like you could stand up right, you feel confident knowing that there are other black people who are into very different things, we don't all look the same, we don't all do the same things. Like having Melissa, for example, who was in the program before I got there and went to Howard: just knowing that there are other people who shared those experiences, you feel confident. Cheyney helped me shake my identity. And I feel like Columbia helped lend that credibility. That's how I could kind of marry the two.

John Pamplin II:

What has been bubbling in my head is that at Columbia, I learned how to be an epidemiologist. But like in terms of being a mentor, I really learned that at Morehouse and the way I approach my students and coursework it's really based on my experiences at Morehouse. Let me tell you that the professor who gives you the easy As is not always looking out for you. And I think we misconstrue that quite a bit. I am also thinking about this whole concept of like the hidden curriculum – I don't know if that's a phrase you folks are more or less familiar with, right? That wasn't something I knew about until graduate school, because at Morehouse they jump off like “All right, here's what you really need to know in addition to this, here's how you need to be prepared for that”. I think about facts like that, as a biology major, I had a required public speaking course, because they knew part of this career is you have to be able to speak. They are not going to leave that up for chance, they are going to make it part of the major as a requirement. Likewise, for business majors at Morehouse, there's a wine tasting event in their junior year. Why? Because they realize you're probably gonna be in these spaces and they want to do everything above and beyond to make sure that the hidden curriculum is not hidden for you. I try to approach that with my students now, and that's one of the biggest things that I try to take away from those joint pieces. Yes, we're going to talk about epic concepts and that's what you're here in my class for. But the mentorship style is something I constantly pull from my experience at Morehouse. Thank you.

Melissa M. Valle:

I think the question a lot of people are curious about is the different experiences at HBCUs and PWIs. Particularly, we're talking about an Ivy League school, not just in any random white institution. Prior to Howard, I had already a diversity of experiences in terms of both class and racially, ethnically. So I grew up in New Jersey. This is gonna sound ridiculous as a sociologist, but it never hit me that I should have known that our school was actually hyper-segregated and we should probably have been bussed – and that actually is one of the reasons that New Jersey has a whole segregation problem. I attended one of those schools, of probably 99% afro-descendant – because it wasn't African American, it was the diaspora. Only now as an adult, I am like "Oh wait, that person's name is Ronaldo da Silva". And everybody was black. So I already had a little bit of that without being aware of it int elementary school, and then I went on to Bloomfield Middle School, which was predominantly Italian and Irish working-class. Then I went on to Columbia High School, which was primarily upper middle class, predominantly white, but also more integrated and a little bit of a model for integrated high schools in America.

And so, for me, it was like “I'm going to go to Howard. I want that experience. I want that beauty. I want, I want that love. And I want that moment in time where, at least I know that if anybody is discriminating against me, it's not because I'm black. As a black person in the United States, it is very rare that you can sort of encounter that space where at least you know they are hating on you for some other reason. There's something else going on. And there, we learned in these spaces that we're not a monolith, there's a diversity of class, there's a diversity of all types of interests, of ways of being. You have elite black folks that are multi generations of coming into these spaces.You have folks who had started from the bottom, and had nothing, but managed to be. Because again, one of the things HBCUs do is giving opportunities to people who wouldn't have had them otherwise. Right? So if you look at things like SAT scores, they're lower because they're also not necessarily basing everything on those test scores, it's more about figuring out how we can bring you through and I would pull you along and get you somewhere else. Same thing when it comes to looking at what people make post-graduation: A lot of people that go to HBCUs are mission-driven, so they work in the service sector, in the public surface sector.

But when it comes to coming to an institution like this, I think part of a gift for a lot of us is that we have to deal with the fact that we do live in this space in the United States and we do in this world where this is a legible institution to people. Which is always difficult to admit. We did this because if I'm looking at sociology, I'm looking at the top programs. Well, let's say you attend Princeton, Michigan and Columbia and all these sort of elite institutions. So I will be honest about the fact I was like “I'm gonna play this game, and I am gonna play it at the top of the pyramid”. But that is also the beauty of having that HBCU experience, still remembering that the majority of people who get PhDs are coming from HBCUs. But it is also important to remind that it's not just that everyone should be at an undergrad HBCU and then go into the Ivy League, because I think that is also a problematic model.

Now that I've had that experience, for almost everything that I do now in life there's one degree of separation from somebody that went to Howard, and if not Howard in another HBCU. How many other opportunities have been built off of just having had that experience that's been sort of built off of just having had that experience. For the rest of your life, no matter what, they will always come back. I remember I was going to make a trip to Ghana by myself and I was like: "Let me hit up the Howard folks”. I ended up living here for 6 months, just because I met a sister who was working there with black and African-Americans moving to Ghana, and then an architect that was at the black market. So we have all of these people, in all of these realms of industry that we can work with as we move on into the spaces that again.

Adina Berrios Brooks:

You all have touched on a lot of my other questions. So I'm going to combine them together, but I'm also going to let everyone know we are going to take questions from the audience. This will be my last question. Please think of questions if you have any questions and ask them to the mic over there. My last question is an advice question and it can be on any of these topics – and some of you have already hit on them: Brittany, you talked about mentoring and networking. 1) If you have any advice about mentorship, finding a mentor, cultivating a relationship with a mentor, etc. 2) For networking strategies – which again, you've hit on a little bit, but I am asking if you have any secret sauce wisdom on that. 3) Resources at Columbia that you found particularly useful that you're willing to share with this crowd: people, organizations. policies, something that you figured out and you want to share that with them.

Taryn Finley:

I will hit on networking because I think that it has been really pivotal in my career and in getting me where I am. I think it's important to not even look at it as networking, because I think when you frame it that there's a stiff air to it, it doesn't feel personable. You can tell when someone is coming up to you trying to connect in a transactional way and that brings anxiety to that person and induces anxiety within yourself – I'm a really anxious girl. I don't even like the term networking, but I know that it is important to do it. Instead, I think about it as cultivating community, making sure that I don't necessarily keep it just to the people who are – quote unquote – above me career-wise, or in places where I want to be, and doing things that I want to do. I think that's important, but I think that it is really great advice to network horizontally. The people sitting next to you in this room, your friends, the people who are like-minded and have similar ideas or even have, you know, different skills that complement yours: those are people who you should be networking with.

And also network with the people who may not be – quote unquote– on your professional level. This goes into mentorship, but I think that it's important to make sure that you're connecting with different generations, in different stages, not only just in your specific area. All around I think that it's important to be curious when you're talking to people and doing that community cultivating because, all in all, even if it doesn't get you to where you want to go, there are so many times when my name has been brought up by people who I met years ago and I'm like “I didn't even know, it, okay, cool, thanks for looking out”. But that's the value and pay off of it. But when you go into it not even necessarily thinking about the end goal, it just feels so much more rewarding. We live in an individualistic society where community is important, especially post Covid people forget to make sure that whatever you do, whatever your intention is, go in a curious, cultivating community.

Brittany fox-Williams:

So I just have two pieces, one about mentoring and one about resources at Columbia. Something that I learned more recently as a faculty member was through the National Center for Faculty, Diversity and Development – and it's something I really held on to. They describe mentoring as like a web. You're not gonna get everything that you need from one mentor. In fact, that's draining on the mentor, but also it's not going to really fulfill exactly what you're looking for. So think about how you can create a web of mentors who can give you different things, right? So say for example you have a mentor who's more of a sponsor, you don't see them often, you don't talk to them often, they're super busy, but they're gonna look out for you behind closed doors. Or think about a mentor who, for example when you're working on your thesis, can actually read your work? Or someone who you can go out to coffee with and have conversations about your career.

So you want to think about having multiple mentors and also think about mentorship coming from not just your peers, or folks who are above you in your career, but also people who could be behind you. For example, I see some of my grad students as mentors in some ways. I learn a lot from them in terms of the new and upcoming research in literature. And I imagine, depending on the career that you're going to, you could think about some of the folks who were coming behind you as being mentors as well. And then the last thing I want to share is a resource at Columbia, which is actually an office, the office of OEDI at GSAS, led by Dr. Celina Chatman Nelson, who I think is here today. Right over there, there she is! But that office was really a safe haven for me at Columbia. It was a place for us to come together as graduate students who were folks of color but who were also interested in similar topics. While I was here at Columbia, we started something called the Diversity Research Collective. For folks who are working on a thesis or a dissertation and you're interested in that collective, it's a phenomenal place to come together with like-minded researchers to work on your projects.

Adina Berrios Brooks:

The first thing you mentioned is also a resource: we are institutional members of the National Center for Faculty Diversity and Development, which we call NCFDD in our office. Their website has lots of tools on mentoring and other topics and it's available for graduate students, post-docs and faculty. It's free through institutional membership if you have with your @columbia.edu account. So definitely check it out.

John Pamplin II:

So I'll definitely echo what Brittany said. I'm a huge fan of mentorship by committee. There is no reason why one person has to do it all for you. I think I would extend upon that to say to look at how people at a more junior career point can also be mentors for you. But I will also note that you don't have to wait till you're at the top of the ladder before you can start looking at yourself as a mentor for those behind you. And I think those relationships can also be really rewarding. When I was a doctoral student, we had a title – it was a joke – but we called it the Mailman Black Epic Caucus, which was essentially myself and the other black doctoral students in the department. And it was literally just kind of when a new student came up to the first year program, we would be like “All right. That's on you, you're responsible for making sure they get past this first year, then you're responsible for this person getting past their second year”. You don't have to wait till you're in that faculty position or you're in that more senior role to start thinking about helping the folks behind you to come through. And then the other resource is not necessarily explicitly a Columbia resource. Just generally: use your community, find ways. There are Columbia specific resources to help find communities, whether it's the different affinity groups or just being creative about it. I think one of the biggest mistakes I made when I first moved to New York was thinking that, just out of undergrad, I wanted to have a new experience. So I intentionally didn't tap into my Morehouse community when I first got here. And it was the most miserable first year of my life. Sometimes even as you do develop community and network within your field, you need to step out of that field. Sometimes you need to move away from it. And really, re-establishing and being in the same way that mentorship doesn't have to be a one side of thing, the community that you pour into does not need to be a single community as well.

Melissa M. Valle:

You said something that I wanted to speak about too. When I arrived here in New York, by the time I started this program at Columbia, I already was sort of a grown up – I was here from 2009 to 2016. And so interestingly enough, when I came in, faculty told me and James Jones, my partner in crime, that we were the first black people ever in the sociology department at Columbia. We did our own research and discovered that actually wasn’t true: there was black faculty before us, and these people actually are doing phenomenal work in the world as sociologists. They were just invisible to you. You didn't see them. They weren't here for you. They didn't matter. Which was kind of how our department worked. And so because of that too, and because of this HBCU background, whenever a black person came in I was like “Let's meet her. Hey, girl, let's meet up”. That relationship is really important, if the people within that department are not going to facilitate things. I remember trying to do this at NYU when I got my MPA I was like ”All right, what programs? Who's here? What's what?”. And they just told me that nothing was happening.

And so I was happy to come here and see that there was a life in one space: and this is where I'm going to give a shout-out to Sharon Harris up in IRS (which is now African American and African Diaspora Studies). That that space was the only one where we could convene, she would have top shelf look at the Christmas event, it was a space that was free and where we could be, and that was a family. In addition to the very rigorous academic work where people are giving talks and having all the top scholars come in, that ended up being a real safe haven, particularly for a few of us in sociology. And we would say “We're going to the holiday party. Let's get the invite”. So part of it is making sure that wherever you are, you're finding those spaces, those networks, even if they aren't necessarily there in your face, you're thinking “Where do we, where do we convene? Where can we be found?”.

One of the keys to getting into this program was something that I learned at Howard: when you're at an institution where four-hundred people go out for Greek life, and for one line you have to do a lot of “Hey, how are you doing? Hey, my name is…”, you have to learn. I look at Greek line here. I thought, “Is this a joke? You don't have to go to any programs? You don't have to know anybody?”. It's just very different. There was a very important networking thing which happened there: you read everyone's bio. You are not going to have a conversation with someone if you didn't know where they were from, what they were doing, what they're about. So when it came time to apply for PhD programs. I was reading people's bios. I was finding that connection. I remember going to a job talk. I read someone's bio. I found that they did this one little stuff, and it was a connection – boom – another connection. And that was the kind of thing that was a straight Howard tool. Is it like you sort of realize how to be in people's faces like “Can I meet you in advance of this thing that I'm trying to do?”. Once you start looking at how many applications go for one program with five slots, you start realizing that you have to somehow differentiate yourself from everybody. A part of that is being an actual face – if you have the luxury of being in the geographical area you can ask to meet. But now in the era of Zoom, can we have a Zoom Meeting so you remember my face and my story. Finding those connections was key in terms of thinking about moving forward and building the career in the life that you really want for yourself.

Adina Berrios Brooks

Thank you so much. Panelists, I hope are staying for the reception and can be chatted with there, and you can tell them a little bit more about your story. Please join me in thanking our wonderful panelists. As I mentioned, right down that hall, there is the World Room, with a very beautiful stained glass window, where we'll be having a reception and hopefully an opportunity to continue these conversations. I want to thank the Office of Alumni and Development. I want to thank my team – I think I saw Diana, Greta, Dror, Vina. Thank you all so much. This is just the beginning. We're hoping to make this an annual event. So if people didn't make it this time, please make sure you tell them that they missed a really great evening. Have a great night.

Pivotal Career Paths and Highlights

Panelists shared highlights from their professional journeys and underscored the profound impact of their educational experiences in shaping their career paths.

Finley, whose aspiration to become a writer was nurtured at Howard, emphasized the significance of dual storytelling, particularly narratives depicting Black culture and experiences. She also discussed the importance of community building, and networking, stressing that she made connections even before her enrollment at Columbia. She appreciated how both schools equipped her with the tools to tell Black stories.

Similarly, Fox-Williams credited her background in business and policy at Cheyney which led her to commercial banking, where she learned valuable skills like professionalism. As a first-generation college student, acquiring these skills was pivotal to her professional growth. Encouraged by her team of women bankers and supported by a fellowship from the United Negro College Fund, she pursued public policy programs and ultimately enrolled at the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA). She noted that Cheyney gave her a sense of self and identity and that Columbia helped lend credibility.

Pamplin II reflected on the transformative impact Morehouse had on his perception of Black identity and his career trajectory, remembering: "I had allowed myself to buy into a very small box of what blackness was. When I stepped foot on that campus it was as if that box was ripped to shreds". He joined Columbia’s Bridge to the Ph.D. Program in STEM, where he met Andrew Davidson, former Vice Provost for Academic Planning, who mentored him into a research career in epidemiology and racial health inequities. He then talked about learning the “hidden curriculum” at Morehouse and how that has influenced how he mentors his students today.

"I had allowed myself to buy into a very small box of what blackness was. When I stepped foot on that campus it was as if that box was ripped to shreds."

Valle traced her journey of translating her passions into meaningful work in the world – a journey that, in her words, is "still ongoing". A double-major in economics and Afro-American Studies at Howard, she received fellowships to continue researching gentrification and public policy and then worked with Human Rights Watch and AmeriCorps. After receiving a Fulbright to conduct ethnographic fieldwork in Colombia, she completed her doctoral studies in sociology at Columbia. She underscored HBCUs’ crucial role in providing opportunities to those who would not have had them otherwise and how those opportunities build off each other.

HB/CU Connections: Networking and Mentorship

Panelists also talked about how they leveraged the benefits of both their HBCU and Columbia degrees, the connections they created, and the importance of networking and mentorship strategies.

Learn more

Finley advocated for creating communities over traditional networking, emphasizing horizontal networking across different generations. Fox-Williams also highlighted the importance of a diverse mentorship network, which she refers to as a web including both peers and students. Pamplin II added that this model of mentorship by committee should also engage with communities outside of one’s field. Drawing on the life skills taught at HBCUs, Valle stressed the significance of finding and creating spaces for connectivity.

Panelists showcased the profound influence of HBCU and Columbia networks in shaping their careers, with a common thread of community, mentorship, and storytelling woven throughout their narratives. Mitchell and Cobb also noted the pivotal influence of these networks, with Mitchell crediting his mentor for instilling “the courage to take up space [...] and make bold decisions,” and Cobb acknowledging: “Out of all of these things that I learned, that confidence was instilled in me”.

These partnerships cultivate mutual growth, nurture impactful research, and create a more equitable and inclusive educational experience. The School of Professional Studies’ fellowship program provides HBCU graduates an opportunity to attend select graduate programs at Columbia and helps integrate scholars into a supportive network. More recently, the Office of Research Initiatives & Development at Columbia formalized a partnership with Southern University and A&M College to facilitate faculty research collaborations and create experiential learning programs. In addition to these exchanges, Columbia will play a vital role in helping to bolster Southern’s grant administration infrastructure and seed research funding efforts.

Overall, the event provided valuable insights, highlighting the power of educational institutions in nurturing talent and fostering meaningful connections that transcend boundaries.