Faculty Profile: Naeem Mohaiemen

Naeem Mohaiemen, Associate Professor of Visual Arts, speaks about the themes of belonging and not belonging, the role of visual archives in geographies ravaged by colonialism and capitalism, and the need for a non-binary, class-embedded understanding of race in the US.

Can you share a bit about your background and your upbringing, and speak to the beginnings of your interest in your work?

I was born in London while my father was attending medical school in Edinburgh. We lived in Clapham Commons. John A. Taylor has just published a history of Winsham Grove, our street, which he describes as home to a West Indian plantation owner, an anti-slavery campaigner, and a corrupt local MP. It was a strange temporary home for my parents. After my father finished his surgery residency, we returned to what was then Pakistan; within one year it became Bangladesh after a liberation war. My family experienced a constant making and unmaking, specific to independence from colonial rule, in the 1960s and 70s. My parents grew up under three flags — as British colonial subjects, then as unequal citizens of Pakistan, and then finally, as Bangladeshi citizens. There was a continuous disruption to the idea of belonging to a single nation-state.

As an army officer, my father was a prisoner of war from 1971-73; he went from being a decorated member of the Pakistan army to belonging to an “enemy country.” We also lived in Libya, a place a lot of migrants from Muslim countries went to in the 70s. We were there along with Polish, Yugoslav-Bosnian, and Jordanian migrants; we learned English as the in-between language, because we couldn't learn Arabic quickly. We lived inside moments where borders shifted and new claims were made on behalf of people sitting inside a geography. Through the uneven learning of language, I was out of time and place–slightly off-sync from where I was supposed to be. I had this sense, always, of belonging and not belonging.

In my family, education was articulated as crucial for the uplifting of the Muslim community; it was a primary tool of emancipation under the British empire and then the Pakistani government as well. I came to the US on a “foreign student” scholarship in 1989, because the anti-army protests in Bangladesh had put Dhaka university into lockdown. I experienced leaving Bangladesh just as the winds of change were arriving in a very dramatic way. Then in the 1990s, our longest-running military government collapsed, and there was a shift where education became less relevant, as the tides of capital came in.

"I wanted to preserve what I could of our sprawling, multi-generation family living under one roof. My father was an obsessive hobbyist photographer, so I held onto his photographs – almost like a raft to prevent myself from drowning."

Bangladesh went through “shock therapy,” liberalizing overnight. One day, you had one black and white TV station from 6pm to 11pm; and then through a licensing land grab, multiple satellite stations. Education became less reliable as a driver of middle class mobility, because the needs of a new economy were something different. Families like ours were swept away, and left behind, by tides of capital-driven liberalization. Coupled with my sense of always feeling out of sync, when market liberalization came in, I wanted to preserve what I could of our sprawling, multi-generation family living under one roof. My father was an obsessive hobbyist photographer, so I held onto his photographs – almost like a raft to prevent myself from drowning.

2001 was a turning point in a different geography; it was the beginning of a new phase of hyper-racialized notions of the Muslim world. The word Muslim is an uneasy racial or ethnic signifier because it's not a category of either, but it became a catch-all in these crisis times. I was a member of Visible Collective, which carried out museum interventions from within that hyper-attenuated subjectivity. "Muslim" was understood to be Arab and South Asian, but the largest number of Muslims in America are African American; so there was a continuous slippage of what “Muslim” meant. Visible Collective asked, as early as 2006, why American media chooses, as public spokespersons of the Muslim-American experience, only South Asian and Arab voices, in a manner that vanishes African American Islam. It is linked to the media-psychological impetus to frame Islam as a “new arrival”, paired with immigration. African American muslims make that lazy “recent immigrant” framing more difficult, especially considering that a large portion of the Atlantic slave trade came from Muslim West Africa.

Growing up in Bangladesh, we resisted religion-based organizing as part of a naive idea of becoming a secular modern. As a migrant to the United States, my Muslim identity is a primary identifier which is very different from the same in Bangladesh, and we hold these conflictual subjectivities in our own bodies, speech, choices, and lives. South Asians in America have had a very complex history with both how they are seen, and how they are seeing an alliance with other communities. In England, “Black British” meant both South Asian and migrants from Jamaica or the West Indies–so “Black” was a supra identity in some ways in 1980s England –– all that has changed with more recent shifts in demographics.

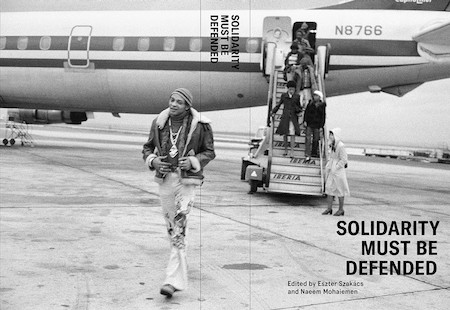

We learned that “Asian American,” as it is framed in the United States, is often meant to refer primarily to East Asia, not to South Asia. And then the insertion of South Asia into Asian America was a political intervention. And then the idea of solidarity with African Americans came out of concepts such as the “third world solidarity” network in the 1970s and then the umbrella term of “people of color” in the 1980s. These are varying, complicated projects of cross-racial solidarity that came out of university campuses, among other sites. It often runs into challenges in the long-term, including the hesitation around bringing class into the conversation–but solidarity is worth fighting for, still. Hungarian curator Eszter Szakacs and myself have been working slowly on an anthology on these themes, titled Solidarity Must Be Defended.

What are the problems or questions that you hope to raise or address in your work?

I have an archive-based research practice which expresses itself through photography, film, and writing. The post-independence archives of many of these countries were not well preserved — sometimes because of preservation technology, and sometimes because someone in power wanted them to disappear. To accomplish this, they had to do no more than neglect; someone in state machinery just had to decline proposals for modernizing libraries. A researcher comes along 20 years later and everything is destroyed by humidity, so it’s non-benign neglect that erases the archive.

So, two paradoxes come up. One is that some of the archive that is preserved is actually in the West, which creates a conundrum: what does it mean to study the archive of the British Empire, for example, in the British Museum or the British Library? You are in some sort of center of power and then you are working through it to create a subaltern discourse, but you are dependent on these institutions for access.

The second paradox is that parts of the archive are missing, so you are filling in the gaps. The witnesses to the archive are often in their last days so you are not able to interview them adequately. English is a default lingua franca of knowledge dissemination in an Anglophone academic sphere, so if you work in a university in those spaces, your narrative of that archive might become a more permanent record than the person who witnessed it, because the person who witnessed it is writing down that history in a language not buttressed by capital-borne hegemony. In post-independence countries, witnesses have not survived for political reasons as well. So there is a stream of writing which is about what would happen if only a certain person had not been assassinated. It can veer into speculative alternative history very quickly.

It sounds like you're approaching your role or responsibility in order to honor, preserve, and interpret the events that you're looking into.

I would like to trouble the framing inherent in this word “honor.” We need to have the space to make histories that are not reverential; because sometimes honoring can be accompanied by an assumption about not saying anything critical about the moment. There has to be some space for criticality because many of these movements we write about were beautiful, but they were also not successful – and in their failures, they opened up disastrous blowback.

What influenced your decision to come to Columbia?

I had done my Ph.D. here, in the Anthropology department, and then was also a postdoctoral fellow at the Heyman Center. So there was a familiarity with Columbia and New York City. The decisive factors were the students and other faculty. I had already worked within the Department of Anthropology and the Institute of Comparative Literature and Society; evolving that relationship to Visual Arts included the idea of making new linkages with those departments, and to Middle East and South Asia Studies. I'm also interested in data science as a category, but I have not figured out where the intersection points are with my teaching.

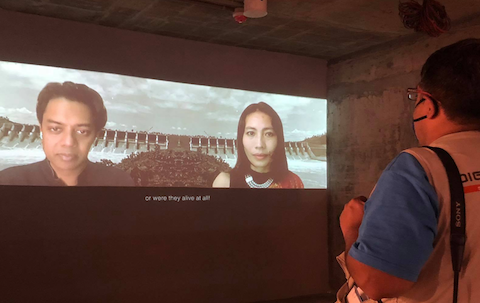

New York occupies a space similar to other entry-point cities. When students graduate and stay on in New York, I hope that collaborations can continue. I just finished a small project with a group of former students: each made a film for their final project and we placed those films in a film festival booklet that came out from the Algeria pavilion of the Venice Biennale. As faculty, we encounter collaborative frameworks; sometimes there is an opportunity to push your students' work because you are working with one set of questions–and then they bring in many multiples of that.

"I think that race, broadly speaking, is understood in the United States in quite binary ways. I would encourage much more of an intermixing of the conversation. There is a whole history of overlaps between different forms of Asian, African American, Indigenous, Muslim, Latinx subjectivities and experiences."

What does it mean to you to be part of this inaugural race and racism cluster hire?

I think that race, broadly speaking, is understood in the United States in quite binary ways. I would encourage much more of an intermixing of the conversation. There is a whole history of overlaps between different forms of Asian, African American, Indigenous, Muslim, Latinx subjectivities and experiences. It seems that sometimes the United States can only imagine one community at a time, as opposed to looking at a centuries long path of hybridization and creolization.

For example, Bengali men who came here in the 1920s married African American and Latinx women and birthed a generation of children who primarily identified as African American during the Jim Crow era. As Vivek Bald has outlined in Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America (2013), South Asians experienced this strange “in-between,” where they were not Black, but they were not White, so they were in a liminal space under segregation.

In Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi (1982), one of the first sequences is Gandhi in South Africa, where he thinks that he can ride on the train, but the official asks: “How did you get a ticket?” And you can see his puzzled face as he says: “But I'm Indian.” He thinks, for a brief moment, that somehow he's not subject to South African law, but he is because he is a “coolie” (a work category signifier and slur) rather than “Indian.” It is a shift, by force, in his understanding of his own racial identity. Gandhi later influenced Martin Luther King with ideas of non-violence, so there are these hybridized overlaps. Communities are always colliding with each other, sometimes through marriage, which is one of the ways that new unions form. Congressman Hansen Clarke, who is primarily seen as a Black politician, has a Bangladeshi father. Kamala Harris is an example of an inter-community union; however, she is also a particular arc because both her parents were academics, so it's also a class-mobility story. I’m interested in conjoining class and race and parsing the venn diagram overlaps and the spaces of friction. I want to understand the white working class and how their contemporary positions of alienation sit alongside the historic disenfranchisement of communities of color. Cedric Robinson's Black Marxism (1983) is an influence; he always argues for bringing class into the foreground of the conversation.

Naeem Mohaiemen’s solo exhibition grace opens at Colby College Museum of Art on November 10th, 2022. It features Jole Dobe Na, a film set in a Kolkata hospital and completed during lockdown for the Raqs Media Collective curated Yokohama Triennale, as well as a collaboration with Karen Wentworth, who advocates for, and may choose to avail herself of, Maine’s Death with Dignity Act. The exhibition includes a video, grace, about Wentworth's daily routine; and an arrangement of works from the Colby Museum's collection chosen by Wentworth and reflective of her interests in photography, folk art, and the elegiac. Mohaiemen was a 2020–21 Senior Fellow at the Lunder Institute of American Art, Colby College, following previous fellows Theaster Gates, Maya Lin, and Romi Crawford.